[ As my dealership grew ] I realized that I was not being challenged anymore in the company, and I wanted to do something else. So I went back to school, and started doing science again.

Kevin Perrott: Then I got cancer of the thyroid, which focused my mind even more. Being a cancer survivor, you’re healthy one day and then you go in for a diagnosis and suddenly you’ve got a terminal disease, but you don’t really feel any different from moment to moment. Absolutely, hands down, it was the best thing that ever happened to me. I wish I could take what I learned from that experience and translate it into other people’s minds, because there would be a lot less confusion about which direction to go if people felt the same way [ about illness ].

Kevin Perrott: Prior to the cancer I was slightly interested in life extension research, but getting cancer was the moment that turned my life around. I was sitting in the hospital, and as bad as my experience was, it was pretty minor, frankly, and there were a whole hospital of people that I had not been aware of prior, going through worse. The medical system, as complex and as much money as it took to run, could do almost nothing except primitive 10-, 20-, 30-, 40-year-old, and sometimes 100-year old therapies. The cavalry was not coming [ I realized ].

SPI: Our readers love science, but life extension hasn’t yet caught on with the general public. What will get it into the mainstream?

Kevin Perrott: People take shelter in the nice fuzzy things about the passage of time, and avoid thinking about how things are when they fall apart. People who object to life extension are obviously not thinking very clearly, because everything is predicated on being alive. Having healthy life is the most important thing.

Kevin Perrott: That became clear to me with my cancer experience. When you’re dead, you’re dead, depending on how much you believe in some afterlife. But even most religious people would opt for a few more days, a few more sunrises, and a few more hugs with their family, than shuffling off this mortal coil.

SPI: Whenever someone mentions death, I put my hands over my ears and go “la la la” until it goes away. So I can see why religion wants to make death sound like you’re just “going to a better place”. Do you get a lot of religious objections to life extension?

Kevin Perrott: I get almost no religious objections. Almost all the objections are secular, economic, or involve equity of treatment.

SPI: So what’s the problem getting support? Do people just not believe that aging research is real?

Kevin Perrott: They don’t even want to believe it’s real, so it’s worse than that. When I came to the realization that we were within maybe a generation or two of actually doing something about the aging process, and I started being optimistic and talking with people about it, the first thing I realized was just how few people think it’s a good idea.

Kevin Perrott: That’s all wrapped up in the psychology of what happens to us when we think about aging. There are two fields of psychology which are emerging. One is called terror management theory, which speaks to how people handle terror. If you’re being held hostage, how do you psychologically manage that, and make an intolerable situation tolerable? Then its subfield is mortality salience theory, the sense for how much time you have before you die.

Kevin Perrott: People are terrorized by death, even though they don’t think about it that way, because it’s an existential angst. They don’t want to think about it. But when they do think about it, they think about it in terms of how much time do I have to do the things that I want to do before I die or before I become decrepit enough that I’m not able to do it.

Kevin Perrott: Those two things combined make aging a unique challenge for government, policy, and science, because it is so instilled in our civilization and culture as something that people don’t want to think about. So it’s very hard to address. You have to find ways of talking about talking about aging with individuals that don’t trigger their psychological defense mechanisms.

SPI: It’s easy to put things off. I always figure there’s going to be a next year. My plan is to be the first person to live forever through sheer stubbornness.

Kevin Perrott: I’ve never had a problem thinking about dying or death. What I don’t like is the suffering that leads up to it, and the fact that we lose the human capital, the equivalent of 100,000 minds every day, the people who die of aging or age-related diseases. Humanity needs to keep older, healthier, wiser people around so that we can get over our more immature tendencies of being too violent, not wanting to share, not cleaning up our mess. All the problems that humanity faces today can be found in the sandbox of schoolyard children who can’t get along.

SPI: So if we help older people to live longer and use their wisdom to help the planet, that’s going to be better for human flourishing.

Kevin Perrott: That’s exactly it. I don’t think we can make headway on some of these perennial problems if we do not also increase the length of time that people have to be alive, and keep people who have acquired that kind of wisdom and experience from being able to exercise that from healthy bodies and positions of vitality. It’s a waste every day.

Kevin Perrott: If you think about what’s happening with global aging, it’s a multinational problem. People are getting older, there are fewer young people, and the talent bubble will collapse if you look at it from an economic perspective. It’s going to be catastrophic on a scale that people don’t want to comprehend, because it’s part of this terror management theory. It’s such an ugly scenario that people don’t even want to discuss it. They can’t discuss it rationally. So this is a good problem for the Secular Policy Institute to solve. Coming at it from a secular policy perspective is the only way to do tackle it because you can’t take refuge away from facts, which you need to solve some of these problems.

SPI: So the Secular Policy Institute can be useful, not because religions object to life extension, but because to understand and prioritize life extension you need a hugely scientific mindset.

Kevin Perrott: You need to have the ability to put aside personal types of biases and look at facts, and take them at face value, even if they don’t necessarily jibe with everything you’re thinking about from a religious perspective. You need people who are unbiased, neutral, and are not swayed by particular modes of thought.

SPI: Obviously everyone should donate to the SENS Research Foundation, LifeStar Institute, Buck Institute for Research on Aging, and Methuselah Foundation Mprize. What else can they do besides giving money, if they want to help?

Kevin Perrott: I think everyone should get educated. We are all patients in waiting. We and the people we love will suffer from degenerative diseases, if we’re lucky enough to live that long. So we need to get as educated as possible and try to read as much as they can about what’s happening in this field.

Kevin Perrott: They can look at any part of the process, whether it’s regulatory, whether it’s basic research, whether it’s in distribution and sales. There are a whole bunch of people, professions, and skills required for that pipeline. And if they don’t have those skills they can advocate and get involved as much as possible. Money is fine, but communication is better, and education is better. I’m happy to be a sounding board and speak with any people interested in this topic. Just tell them to contact me at kevin@kevsplace.net.

SPI: Thank you for you time.

Kevin Perrott: Thank you, too.

On December 10,┬á┬áUK women’s rights groups supported by┬áSPI Advocate Maryam Namazie┬áhand delivered a letter signed by nearly 400 individuals and organisations to urge┬áBritish Prime Minister David Cameron to formally look into the discriminatory nature of Sharia ÔÇÿcourtsÔÇÖ and other religious arbitration forums. They want to stop Sharia, the Jewish Beth Din, and other kinds of religious ‘courts’ from having sway over family matters including divorce.

On December 10,┬á┬áUK women’s rights groups supported by┬áSPI Advocate Maryam Namazie┬áhand delivered a letter signed by nearly 400 individuals and organisations to urge┬áBritish Prime Minister David Cameron to formally look into the discriminatory nature of Sharia ÔÇÿcourtsÔÇÖ and other religious arbitration forums. They want to stop Sharia, the Jewish Beth Din, and other kinds of religious ‘courts’ from having sway over family matters including divorce. SPI Fellow Elham Manea has been active as the spokesperson for jailed Saudi blogger Raif Badawi. And she’s written on behalf of gay men killed in Yemen on the Huffington Post, saying it shows alarmingly how powerful Al Qaeda and Islamic State in that country. She is an Associate Professor at the Institute of Political Science, University of Zurich, Switzerland and a dual-citizen of Yemen and Switzerland. She recently contributed recommendations for how Western governments should handle proponents of Sharia Law in the legal systems for the SPI World Future Guide 2016, the Secular Policy Institute’s original policy recommendations for decision-makers around the globe.

SPI Fellow Elham Manea has been active as the spokesperson for jailed Saudi blogger Raif Badawi. And she’s written on behalf of gay men killed in Yemen on the Huffington Post, saying it shows alarmingly how powerful Al Qaeda and Islamic State in that country. She is an Associate Professor at the Institute of Political Science, University of Zurich, Switzerland and a dual-citizen of Yemen and Switzerland. She recently contributed recommendations for how Western governments should handle proponents of Sharia Law in the legal systems for the SPI World Future Guide 2016, the Secular Policy Institute’s original policy recommendations for decision-makers around the globe. Congratulations to SPI Fellow Marty Klein for being the keynote speaker at the National Sex Education Conference this month in New Jersey. He has many speeches coming up in 2016, including in California, Texas, and Illinois. He’ll talk about pornography, cybersex, and how therapists can talk sex to their patients. He encourages you to give sex for the holidays by purchasing one of his books, CDs, or downloads on modern sexuality from a secular perspective. Through December 31 you can use code V20 for a 20% discount on his website store.

Congratulations to SPI Fellow Marty Klein for being the keynote speaker at the National Sex Education Conference this month in New Jersey. He has many speeches coming up in 2016, including in California, Texas, and Illinois. He’ll talk about pornography, cybersex, and how therapists can talk sex to their patients. He encourages you to give sex for the holidays by purchasing one of his books, CDs, or downloads on modern sexuality from a secular perspective. Through December 31 you can use code V20 for a 20% discount on his website store.

So what are the trends? By

So what are the trends? By

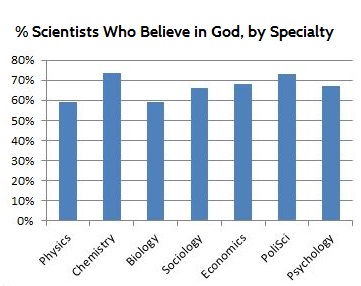

Also, some countries surprisingly had scientists who were more religious than the general purpose, the reverse of expectations. For example, 39% of Hong Kong scientists but only 20% of Hong Kong residents are religions, and 54% of Taiwanese scientists but only 44% of Taiwanese are religion.

Also, some countries surprisingly had scientists who were more religious than the general purpose, the reverse of expectations. For example, 39% of Hong Kong scientists but only 20% of Hong Kong residents are religions, and 54% of Taiwanese scientists but only 44% of Taiwanese are religion. Or try the

Or try the  At a more professional level,

At a more professional level,  Atheist Ireland

Atheist Ireland A week after ISIS pulled off a bloody terrorist attack in Paris, a group affiliated with al-Qaeda kills 20 people in Mali

A week after ISIS pulled off a bloody terrorist attack in Paris, a group affiliated with al-Qaeda kills 20 people in Mali In our new and original report, the

In our new and original report, the  SPI Fellow

SPI Fellow  And SPI Fellow

And SPI Fellow  In the United States, the

In the United States, the  The

The  And the

And the