The weekly report on research and demographics of the secular movement

by Julie Esris

Do you need to believe in God to be Jewish? Not at all, says Benjy Cannon, who penned an article describing his journey from modern Orthodoxy to atheism, all while retaining his Jewish identity. The article, which appeared in Haaretz last week, is the latest in a series of stories about once-religious people renouncing their faith. However, it is CannonÔÇÖs retaining ofÔÇöand treasuringÔÇöhis cultural roots that sets his story apart from others. More specifically, the story is set apart from those about ex-Muslims, ex-Christians, and others who have left a variety of religions.

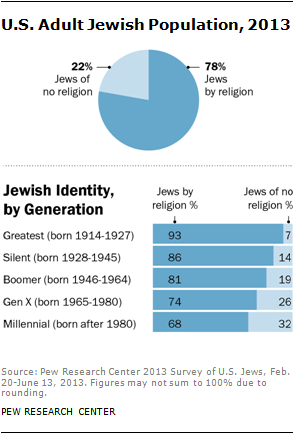

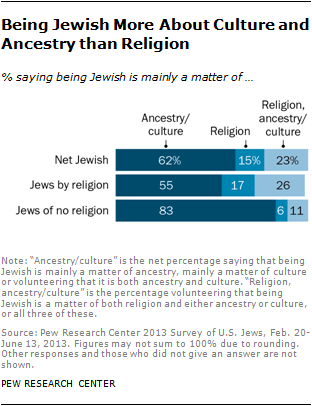

It is indeed very common for atheists brought up Jewish to identify as Jewish; they value the cultural traditions divorced from the religious aspect. In fact, a 2013 Pew study confirms this: 22% of American Jews also describe themselves as atheists. The percentage of American adults who call themselves Jewish is just under 2%, a significant decline since the 1950s. However, the percentage of those who describe themselves as culturallyÔÇöbut not religiouslyÔÇöJewish is on the rise, and makes up about 0.5% of the American adult population. Analysis by generation also confirms a decline of religiosity in self-identified Jews. 93% of American Jews born in the early twentieth century identify as religiously Jewish, versus 7% who identify as Jewish without the religious aspect. This stands in stark contrast to the Millennial (youngest adults) generation of Jews, 68% of which identify as religiously Jewish, versus 32% who identify as Jewish without the religious aspect.

The decline in Jewish religiosity in America reflects a decline in religiosity as a whole. However, as Benjy Cannon illustrates, there seems to be something unique to Judaism in which cultural identity is not necessarily dependent on religious belief. It is also worth noting that Secular Policy InstituteÔÇÖs Secular Resource Guide lists ÔÇ£secular JewsÔÇØ as a group of people who are part of the religious decline in America. In this report, however, there are no groups of people identified as ÔÇ£secular ChristiansÔÇØ or ÔÇ£secular MuslimsÔÇØ. It seems to be significantly more common to hear terms like ÔÇ£atheist JewÔÇØ or ÔÇ£Jewish atheistÔÇØ than ÔÇ£atheist ChristianÔÇØ (or Muslim, or any other religious label). The question is why.

Benjy Cannon notes in his article that despite having been raised in modern Orthodox culture, his religious schoolteachers encouraged questioning. One teacher even said that evidence strongly indicates that multiple authors wrote the Torah over the course of hundreds of years. With the exception of Ultra-Orthodox sects, Judaism has a widespread reputation of being part of an intellectual, educated culture. Perhaps the Jewish cultureÔÇÖs strong emphasis on education originated as a coping mechanism in the face of centuries of oppression and persecution that Jews have endured (Armenians, another historically persecuted culture, have a similar reputation of highly valuing education). With education comes questioning, which in turn makes it easier to lose oneÔÇÖs religious beliefs. But if education is an important part of the Jewish culture, why would a religious Jew-turned-atheist turn his back on the culture that, perhaps, indirectly led him to atheism?

Today Benjy Cannon and other Jewish atheists continue to gather with one another for Jewish holidays and other culturally Jewish activities. It gives Cannon and others like him a sense of community with rich tradition without invoking the supernatural. As Cannon put it, he practices his form of Judaism for his community, not for God.