The weekly report on research and demographics of the secular movement

by Julie Esris

It is common knowledge that strong religious beliefs positively correlate with the rejection of scientific consensus, particularly in terms of evolution and climate change. It is tempting to conclude that science denial is entirely religionÔÇÖs fault, but there are also religious people who accept both evolution and climate change. In fact, there may be other ideological factors at play. Examining political beliefs in addition to religious beliefs may elucidate just how ideology plays into the acceptance or rejection of evolution and climate change, particularly in America.

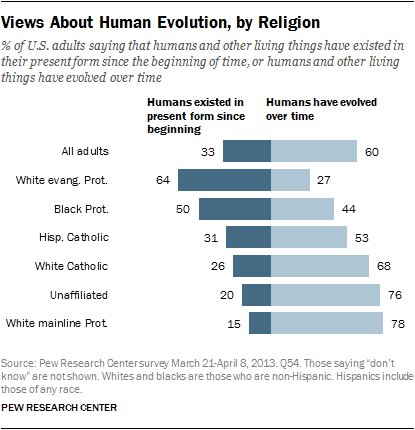

A 2013 Pew study reveals that only 60% of Americans accept evolution. Of American Christian groups surveyed, mainline Protestants are most likely to believe in evolution, at 78%. The religiously unaffiliated are slightly less likely, at 76%. 68% of white Catholics and slightly fewer Hispanic Catholics (53%) accept evolution. The two groups that are the most likely to reject evolution are black Protestants (44%) and white evangelical Protestants (27%).

It is surprising that the religiously unaffiliated are slightly less likely to accept evolution than white mainline Protestants. However, the percentages are so similar that it might not even be worth considering: perhaps polling more people from these groups would yield slightly different results. Except for white evangelical Protestants, black (presumably) non-evangelical Protestants are the most likely to reject evolution. This could be due to of perceived racism of Darwinism: Sometimes people with racist agendas distort evolutionary theory, dismissing blacks as ÔÇ£less evolvedÔÇØ than and inferior to whites. Additionally, many people fear that evolution could be used as justification for persecuting minorities and people with disabilities. It is a common misconception that acceptance of evolution fueled the Holocaust when, in fact, On the Origin of Species was among the books banned in HitlerÔÇÖs Germany.

But what of climate-change denialism?

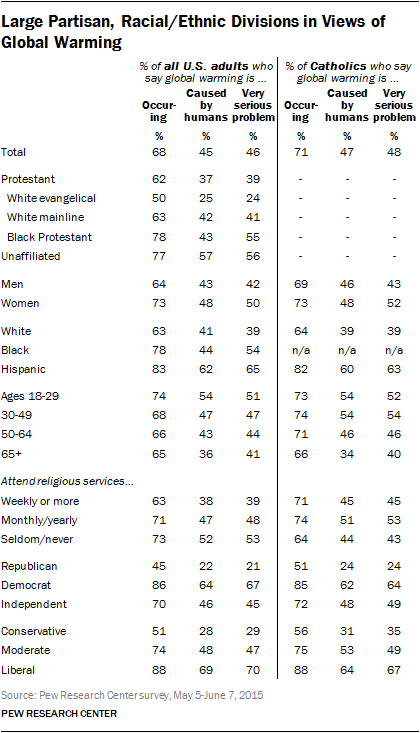

A Pew study released last week surveyed the same Christian groups about their views on climate change. Unsurprisingly, at 77%, the religiously unaffiliated are among the most likely to accept climate change (the average acceptance among the general public is 68%). Black Protestants accept it at a slightly higher rate, at 78%. 63% of white mainline Protestants believe in climate change versus 50% of white evangelical Protestants. At 71%, Catholics are more convinced of climate change than almost any Christian group. However, this poll also illustrates that acceptance of climate change is more influenced by race and political beliefs than by religious beliefs. In fact, blacks are the ethnic group most likely to accept climate change. While it is true that the religious are more likely to reject it, they are also more likely to vote for Republican politicians, who accept climate change at a much lower rate than Democrats.

It is curious that race plays a role in oneÔÇÖs views on climate change. As with blacksÔÇÖ reluctance to accept evolution, it could be that their viewpoint has its roots in historic injustices. Perhaps it is the manifestation of a certain cynicism, a suspicion about rich and powerful white people, often the CEOs of corporations that are responsible for damaging the environment. It is also possible blacksÔÇÖ acceptance of climate change could be due to the fact that an overwhelming majority of them vote for members of the Democratic Party, whose members are more likely to believe in climate change.

It makes sense that the religiously unaffiliated are the most likely to accept evolution (76%)ÔÇöwithout religious dogma, they are receptive to the scientific consensus that evolution is a fact. While this level of acceptance of climate change (77%) is similar to that of evolution, it is also important to know that this group of people largely votes Democrat. Moreover, it seems that acknowledgement of this issue in the general population is not based on examining the evidence but rather political leanings. There may even be a similar phenomenon in terms of oneÔÇÖs views about evolution. After all, it is possible to be an atheist as unthinkingly as it is to be a religious zealot. Some people may accept evolution merely because it is intrinsically contrary to religion, not because overwhelming evidence confirms its veracity. If there is one important lesson to learn from these studies, it is the importance of putting aside fearsÔÇöhowever understandableÔÇö and ideologies when drawing conclusions about such divisive issues.