The weekly report on research and demographics of the secular movement

by Julie Esris

It is very tempting to assume that all Arabs are Muslim, and that most of these Muslims are extremists. However, this is simply not true. Recently, New Republic published an article about the so-called ÔÇ£invisibleÔÇØ atheists, Arab non-believers who have renounced Islam. It is not easy to leave Islam in the Middle East. First of all, the punishment for apostasy is death. Although the death penalty for apostates is rarely enforced, punishment can still be quite severe, in the form of imprisonment and lashes. Then, of course, are the fatwas issued, in which Muslim leaders call for the death of apostates. Some atheists in the Middle East have been open about their non-belief on Facebook, Twitter, and blogsÔÇöat great risk to themselves. Why is it so difficult to be an atheist in so many Middle Eastern countries? Are there really fewer atheists in Arab countries than elsewhere, or do these atheists just lie in order to protect themselves from harm? Or is it a combination of the two? And as for Arabs who do practice Islam, just how religious are they?

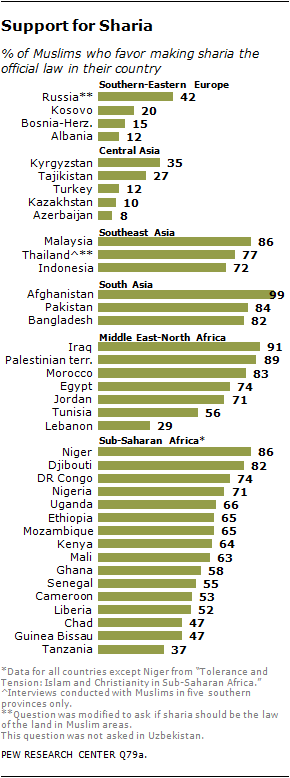

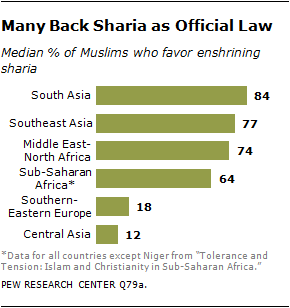

A 2013 Pew poll helps answer these questions. The study surveyed 38,000 Muslims in 39 countries in six regions: Southern and Eastern Europe, Central Asia, Southeast Asia, South Asia, the Middle East and North Africa, and sub-Saharan Africa. Those surveyed were asked about whether or not they support sharia (Islamic) law. As one would expect, significant percentages of Muslims in many countries want sharia law to be the law of the land. Support for sharia is the highest in South Asia with a median of 84%, followed by Southeast Asia at 77%. Middle East and North Africa follow at 74%, Sub-Saharan Africa at 64%, Southern-Eastern Europe at 18%, and Central Asia at 12%. These are averages for an entire region, however, and when broken down by individual countries, the top three supporters of sharia law are in the Middle East. Afghanistan ranks with the highest support of sharia law (99%), followed by Iraq (91%), and then the Palestinian territories at (89%). In most of the countries surveyed, support for sharia law varies little by age, gender, or education.

With these numbers, it is unsurprising that very few Arabs will admit to their atheism. The New Republic article cited a poll that suggests that there are only 2,293 Arab atheists out of a population of 300 million. The poll is likely a reflection on how dangerous it is for Arabs to be openly atheistic. The poll claimed that Egypt is home to 866 atheists, Morocco to 325, Tunisia to 320, Iraq to 242, Saudi Arabia to 178, Jordan to 170, Sudan to 70, Syria to 56, Libya to 34, and Yemen to 32. As previously noted, sharia law calls for death as the punishment for apostasy, with imprisonment being the most common sentence enacted.

However, it is interesting to note is that while apostasy is taboo in much of the Arab world, many Arabs are also not as religious as weÔÇöor even theyÔÇöthink they are. There are some secular lifestyles and attitudes that are, surprisingly, tolerated in the Arab world. Drinking alcohol is common despite being forbidden in Islam. Islam requires that adherents pray five times a day at fixed times, including twice during work hours, but many people skip these two prayers and do them later at home. In Saudi Arabia, a country that is very extreme in its implementation of religious protocol, shops close for fifteen minutes during each prayer call. However, instead of praying, many people gather outside the shops to smoke cigarettes or just to await the shopsÔÇÖ reopening. Even sex outside of marriage is common in Arab countries, particularly in urban areas. In short, people are not necessarily required to be religious but are expected to define themselves as Muslims, which covers a variety of levels of observance.

While it is still very difficult to be an atheist in the Arab world, the good news is that some secularism, albeit very little, is finding its way into everyday life. Additionally, with the advent of the Internet, many young Arabs are becoming exposed to other ideas that make them begin to question the theology with which they were brought up. Although risky, they are able to meet other Arabs online who have similar doubts and who have rejected religion altogether. Perhaps these are signs of an impending cultural revolution.