US presidential candidate Marco Rubio was taking questions from an audience this week when an atheist asked him about his faith. He responded, “No oneÔÇÖs going to force you to believe in God. But no oneÔÇÖs going to force me to stop talking about God… You shouldnÔÇÖt be worried about my faith influencing me. You should hope that my faith influences me.ÔÇØ

US presidential candidate Marco Rubio was taking questions from an audience this week when an atheist asked him about his faith. He responded, “No oneÔÇÖs going to force you to believe in God. But no oneÔÇÖs going to force me to stop talking about God… You shouldnÔÇÖt be worried about my faith influencing me. You should hope that my faith influences me.ÔÇØ

Why do politicians in the United States emphasize religion so much? Conservative candidate Ted Cruz even said in November that atheists aren’t moral enough┬áto be president:┬á”Any president who doesn’t begin every day on his knees isn’t fit to be commander-in-chief of this country.”

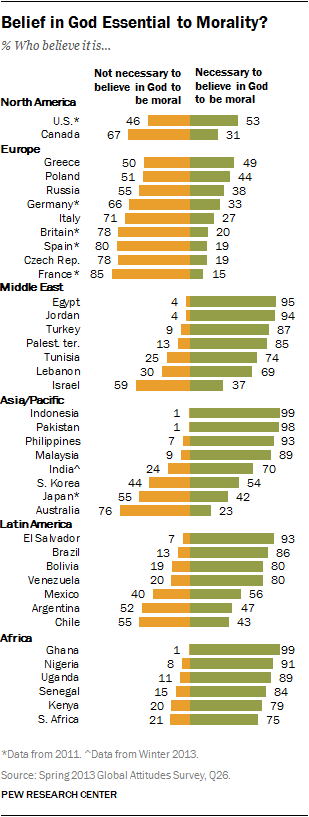

A common question in religious discourse asks whether belief in the divine makes one behave better or worse; or, more precisely, whether religious belief is essential to ascertaining objective morality. A Pew Global study in 2014 showed that more than half of Americans (53%) believe that it is ÔÇ£necessary to believe in God to be moralÔÇØ. Such an approach has likely had a significant impact on American policy-making. Indeed, which aspiring Presidential candidate could conceivably build an electoral campaign without professing a belief in the supernatural ÔÇô a position essential to achieving an objective morality for 53% of PewÔÇÖs respondents?

A common question in religious discourse asks whether belief in the divine makes one behave better or worse; or, more precisely, whether religious belief is essential to ascertaining objective morality. A Pew Global study in 2014 showed that more than half of Americans (53%) believe that it is ÔÇ£necessary to believe in God to be moralÔÇØ. Such an approach has likely had a significant impact on American policy-making. Indeed, which aspiring Presidential candidate could conceivably build an electoral campaign without professing a belief in the supernatural ÔÇô a position essential to achieving an objective morality for 53% of PewÔÇÖs respondents?

A profession of religious belief, and thus divinely oriented morality, allows a leader ÔÇô whether Presidential, Senatorial, etc. ÔÇô to claim a level of moral authority. It is likely for this reason that the faithful reliably vote for the candidate which they know will stringently adhere to religious doctrine. Take this 2012 study by Pew Research, for example, which demonstrates the trend. 79% of evangelicals voted for Romney; 69% of white Protestants also voted for the former GOP nominee. However, in making a claim to objective morality, religious leaders claim to represent everyone. This leaves the 22.8% of the religiously unaffiliated demographic (as defined in this Religious Landscape study) unrepresented at the governmental level, disempowered by the refusal of irreligious politicians to vocalize their worldview in fear of political or social ostracism.

From a policy perspective, this is troublesome. Just as interreligious differences lead to competing policy directions (the Muslim lobby is likely to attempt to impede the US-Israeli relationship, for example), differences between the secular and religious worldviews can also foment friction. Take Bush Jr., whose ÔÇÿfaith-based initiativesÔÇÖ sought to (among various other things) strengthen the legislative pro-life stance on abortion. This is likely to be in direct conflict with the secular approach, which tends to endorse a scientific evaluation of the pro-life v pro-choice debate. Indeed, in this poll conducted by Gallup in 2012, it was demonstrated that just 19% of non-religious Americans find themselves on the pro-life side of the table. And thus the antagonism is highlighted: while religious leaders claim divinely mandated and universal morality, some, such as Bush Jr., also pursue policies which counter the secular worldview. It can reasonably be said, then, that religious leaders cannot represent an entire nationÔÇÖs demographic.

Pew has identified that just 0.2% of the 115th Congress is religiously unaffiliated. This, compared to a nationwide average that sits at around 20% is at best a statistical anomaly; at worst, a patent failure to represent the publicÔÇÖs interests. The secular position does not equate religious belief with morality or immorality. Instead, it favours a rational, objective evaluation of a politicianÔÇÖs motives and legislative performance. The non-religious deserve recognition and representation in the political system. Endeavouring to evolve attitudes which relate to the cast-iron incremental relationship between religious belief and morality is therefore a crucial step towards a more representative political landscape.