The Weekly Numbers Report

by Deanna Cantrell

For many, including myself, science served as not only a resource to quench unending curiosity about the mechanics of the universe, origin of species, as well as countless other burning questions about the world we live in as well as the cosmos; science also served as a starting point of my own secular journey.  In years since, meeting countless others who share the same world view, I have found that I am not alone.  Many secularists begin questioning faith through scientific fact.  If x is true, then how can y be true if they contradict?  Is the same true for scientists?  What about philosophers?  Can those immersed in a field where faith is in direct contradiction with fact manage to hold on to belief?

For many, including myself, science served as not only a resource to quench unending curiosity about the mechanics of the universe, origin of species, as well as countless other burning questions about the world we live in as well as the cosmos; science also served as a starting point of my own secular journey.  In years since, meeting countless others who share the same world view, I have found that I am not alone.  Many secularists begin questioning faith through scientific fact.  If x is true, then how can y be true if they contradict?  Is the same true for scientists?  What about philosophers?  Can those immersed in a field where faith is in direct contradiction with fact manage to hold on to belief?

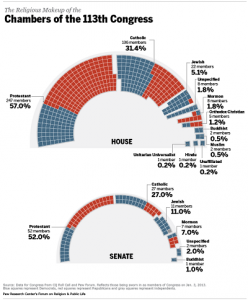

It is widely accepted fact that politics and religious affiliation are part in parcel.  Even though politicians are sworn to uphold the Constitution and keep their personal beliefs at home, it is clearly seen that the majority of politicians try to appeal to certain demographics come election time.

uphold the Constitution and keep their personal beliefs at home, it is clearly seen that the majority of politicians try to appeal to certain demographics come election time.

Just this week, in news regarding the ongoing saga of Kim Davis, Kentucky County clerk who was jailed for contempt of court after ignoring repeated court orders to issue marriage licenses to same sex couples, Kentucky Senator Rand Paul came to her defense.┬á He previously called putting Davis in jail was ÔÇ£absurd.ÔÇØ ┬áHe said, ÔÇ£I think itÔÇÖs a real mistake and even those on the other side of the issue, I think it sets their movement back,ÔÇØ Paul said.┬á Governor Mike Huckabee, Louisiana Governor Bobby Jindal, and Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker were also among supporters for Davis.

Curious about the affiliation of your representative?

The Kim Davis story raises a basic question: To what extent should we allow people to break the law if their religious views are in conflict with it? ItÔÇÖs possible to take that question to an extreme that even Senator Paul might find absurd: imagine, for example, a jihadist whose interpretation of the Koran suggested that he should be allowed to behead infidels and apostates. Should he be allowed to break the law? OrÔÇöto consider a less extreme caseÔÇöimagine an Islamic-fundamentalist county clerk who would not let unmarried men and women enter the courthouse together, or grant marriage licenses to unveiled women. For Rand Paul, what separates these cases from Kim DavisÔÇÖ? The biggest difference, I suspect, is that Senator Paul agrees with Kim DavisÔÇÖs religious views but disagrees with those of the

The line between theism and politics may be an easy one to draw; the United States, for now, still holds a theistic majority in population with 78.3% identifying with some sort of faith.  Elections are about policy, but the ugly truth is that they are also a popularity contest.  What about those who rely on just fact?  How many philosophers and scientists manage to keep the faith?

To quote Lawrence Krauss in his new article, All Scientists Should Be Militant Atheists

In science, of course, the very word ÔÇ£sacredÔÇØ is profane. No ideas, religious or otherwise, get a free pass. The notion that some idea or concept is beyond question or attack is anathema to the entire scientific undertaking. This commitment to open questioning is deeply tied to the fact that science is an atheistic enterprise. ÔÇ£My practice as a scientist is atheistic,ÔÇØ the biologist J.B.S. Haldane wrote, in 1934. ÔÇ£That is to say, when I set up an experiment I assume that no god, angel, or devil is going to interfere with its course and this assumption has been justified by such success as I have achieved in my professional career.ÔÇØ ItÔÇÖs ironic, really, that so many people are fixated on the relationship between science and religion: basically, there isnÔÇÖt one. In my more than thirty years as a practicing physicist, I have never heard the word ÔÇ£GodÔÇØ mentioned in a scientific meeting. Belief or nonbelief in God is irrelevant to our understanding of the workings of natureÔÇöjust as itÔÇÖs irrelevant to the question of whether or not citizens are obligated to follow the law.

Faith can exist among the scientific community.┬á The human mind has an amazing power to compartmentalize.┬á Perhaps faith can be such a part of the fabric of a person’s identity that no matter how much knowledge one has to disprove the existence of a deity, one’s faith can managed to be tucked away in a safe place.┬á A place impermeable to data, theory…a sort of God-shaped box. [52] Leading Scientists Still Reject God, Edward Larson and Larry Witham, Nature, July 1998. [53] What Do Philosophers Believe? David Bourget and David Chalmers, November 2013 Footnotes courtesy of the SPI Secular Resource Guide

How do the numbers measure up to Mr. Krauss’ thesis?┬á A survey of scientists who are members of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, conducted by the Pew Research Center for the People & the Press in May and June 2009, finds that members of this group are, on the whole, much less religious than the general┬ápublic.┬á Indeed, the survey shows that scientists are roughly half as likely as the general public to believe in God or a higher power. According to the poll, just over half of scientists (51%) believe in some form of deity or higher power; specifically, 33% of scientists say they believe in God, while 18% believe in a universal spirit or higher power.┬á As for philosophers, 93% either doubt God or disbelieve in God, up from an astonishing 85% in 1933 and 73% in 1914

How do the numbers measure up to Mr. Krauss’ thesis?┬á A survey of scientists who are members of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, conducted by the Pew Research Center for the People & the Press in May and June 2009, finds that members of this group are, on the whole, much less religious than the general┬ápublic.┬á Indeed, the survey shows that scientists are roughly half as likely as the general public to believe in God or a higher power. According to the poll, just over half of scientists (51%) believe in some form of deity or higher power; specifically, 33% of scientists say they believe in God, while 18% believe in a universal spirit or higher power.┬á As for philosophers, 93% either doubt God or disbelieve in God, up from an astonishing 85% in 1933 and 73% in 1914